|

|

In Memoriam |

|

|

|

||

|

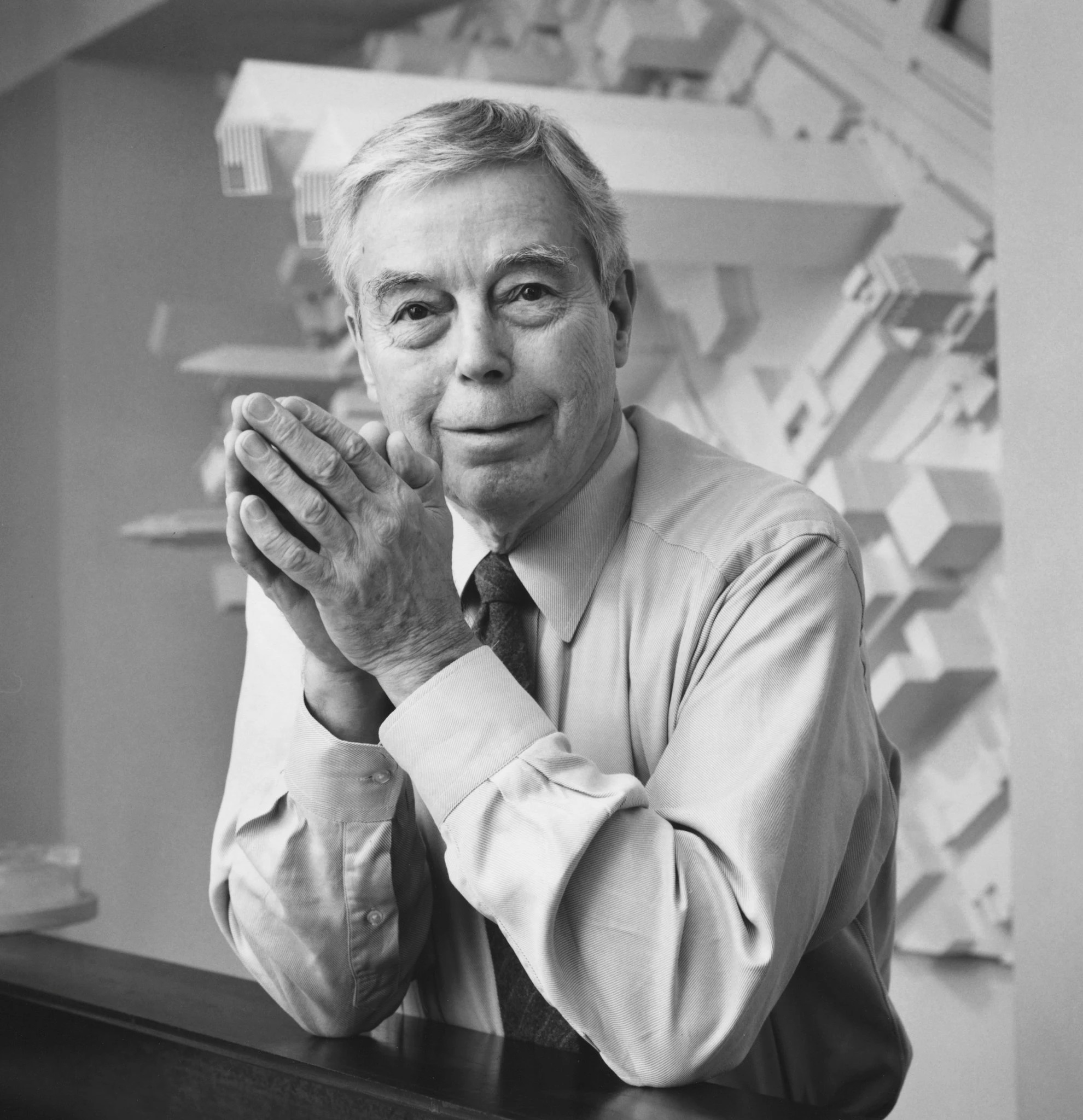

Leslie E. Robertson February 12, 1928 - February 11, 2021 Obituary Leslie E. Robertson, the structural engineer of the World Trade Center, whose work came under intense scrutiny after the complex was destroyed in the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, died on Thursday at his home in San Mateo, Calif. He was 92. The death was confirmed by his daughter Karla Mei Robertson. She said he had received a diagnosis of blood cancer a year ago.

Mr. Robertson designed the structural systems of several notable skyscrapers, including the Shanghai World Financial Center, a 101-story tower with a vast trapezoidal opening at its peak, and I.M. Pei’s Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, a cascade of interlocking pyramids. His projects included bridges, theaters and museums, and he helped install sculptures by Richard Serra, some weighing as much as 20 tons. But the project that came to define his career was the World Trade Center. He was in his early 30s and something of an upstart when he and his partner, John Skilling, were chosen to design the structural system for what were to be the time, at 110 stories, the world’s tallest buildings. He was in his 70s when the towers were destroyed. Mr. Robertson, who had no experience with high-rises when he began working on the World Trade Center, recalled that Mr. Skilling had wanted him to team up with Anton Tedesko, “an older and more experienced man.” But Mr. Robertson refused, an “act of brinkmanship on my part,” he recalled in a memoir, “The Structure of Design: An Engineer’s Extraordinary Life in Architecture” (2017).

He had developed “a lot of good ideas for the project,” he wrote, “and didn’t want to have to turn to anyone for their filtering or further development.” With some reluctance, he recalled, Mr. Skilling agreed to let him run the project. “The responsibility for the design ultimately rested with me,” Mr. Robertson told The New York Times Magazine after the towers were destroyed. He added: “I have to ask myself, Should I have made the project more stalwart? And in retrospect, the only answer you can come up with is, Yes, you should have.” He conceded that he had not considered the possibility of fire raging through the buildings after a plane crash. But he also said that that was not part of the structural engineer’s job, which involves making sure that buildings resist forces like gravity and wind. “The fire safety systems in a building fall under the purview of the architect,” he said. In an interview in 2009 in his Lower Manhattan office, Mr. Robertson wiped away tears as he recalled the victims of 9/11. He talked about the family members who had come to see him, hoping he could say something to help them with their grief. But he also said he was proud of the design of the twin towers. The World Trade Center was first attacked by terrorists in 1993, when a bomb exploded in an underground parking garage. Six people died and more than 1,000 were injured. After that blast, which did no major damage to the buildings beyond the garage, Mr. Robertson made television appearances. “I felt that it was necessary to step forward and explain that the buildings were safe,” he said, “and I did that.” The attack eight years later had a very different outcome.

Mr. Robertson was in

Hong Kong when the buildings were hit by planes loaded

with jet fuel. Members of his firm — including his wife,

SawTeen See, also a structural engineer — watched the

destruction from the windows of their offices just a few

blocks away, at 30 Broad Street.

According to Mr. Robertson, the buildings had been designed to withstand the impact of a Boeing 707, but the planes flown into the towers were heavier 767s. And his calculations had been based on the initial impact of the plane; they did not take into account the possibility of what he called a “second event,” like a fire.

When the planes

struck the towers, they sliced through the steel frames,

but the buildings remained standing. Many engineers

concluded that conventionally framed buildings would

have collapsed soon after impact. The twin towers stood

long enough to allow thousands of people to escape.

Mr. Robertson said he

received hate mail after 9/11. But on a flight to

Toronto one day, an airline employee gave him an

unexpected upgrade to first class. When he asked for an

explanation, he recalled in the 2009 interview, the

employee said, “I was in Tower 2, and I walked out.”

But Mr. Robertson

could not escape the images of that terrible day: “My

sense of grief and my belief that I could have done

better continue to haunt me,” he wrote in “The Structure

of Design.” His parents divorced when Mr. Robertson was a boy, and he was raised by his father’s second wife, Zelda (Ziegel) Robertson, also a homemaker. In 1945, when he was 17, Leslie lied about his age and joined the Navy. He was not deployed, and he was honorably discharged that September. He studied engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, receiving a bachelor of science degree in 1952. Over the next six years he worked as a mathematician, an electrical engineer and a structural engineer; for a time, while living in New York, he investigated the collapse of an offshore drilling platform. When that job ended, he decided to head west to California with his family in a Volkswagen convertible. The money ran out in Seattle, and in 1958 he took the first job he could get, at Worthington and Skilling, a structural engineering firm. Its clients included the Seattle-born architect Minoru Yamasaki, who had several projects in that city. In 1962, Mr. Yamasaki won a competition to design the World Trade Center, and he helped Mr. Robertson’s firm obtain the engineering contract. “What that man did to me was incredible,” Mr. Robertson said. “I was a kid, and he said, ‘Go for it.’” He added: “We had never done a real high-rise project before.” Mr. Yamasaki felt that tall buildings were uncomfortable to be in unless they provided a sense of enclosure. It was that notion that led to the tube design, with exterior columns about two feet apart for most of the buildings’ height. Mr. Robertson moved to New York to work on the Trade Center; Mr. Skilling stayed in Seattle. (He died in 1998.) In 1982, the firm — by then known as Skilling, Helle, Christiansen, Robertson — broke up, and its New York office became Leslie E. Robertson Associates, later LERA. Mr. Robertson gave up his partnership in 1994 but worked on the firm’s projects until 2012. His first two marriages, to Elizabeth Zublin and Sharon Hibino, ended in divorce. He married SawTeen See, an engineer and later managing partner of LERA, in 1982. She survives him. In addition to her and their daughter, Karla Mei, he is survived by a son, Chris, from his first marriage; a daughter, Sharon Robertson, from his second marriage; and two grandsons. Another daughter from his first marriage, Jeanne Robertson, died of breast cancer in 2015. When he landed the World Trade Center project, Mr. Robertson was “a hotshot who had dismissed the entire East Coast engineering establishment as calcified” and had “set out to do no less than change the principles of skyscraper design,” according to The Times Magazine.

“We were younger — we

were not burdened with all of the baggage of how

buildings had been constructed in the past,” Mr.

Robertson said. “In a sense, we were the perfect

choice.”

|

In Memory of

In Memory of